Character Archetypes in Fiction: The Timeless Building Blocks of Storytelling

Dive into timeless character archetypes, understanding their foundation in storytelling and how to blend or subvert them to create complex, engaging characters.

WRITING & EDITING

Character Archetypes in Fiction: The Timeless Building Blocks of Storytelling

Introduction: What Are Character Archetypes and Why Do They Matter?

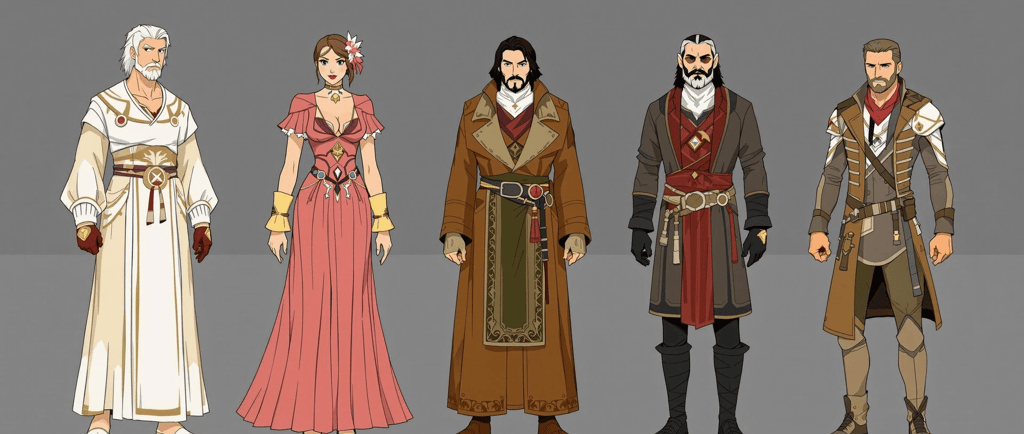

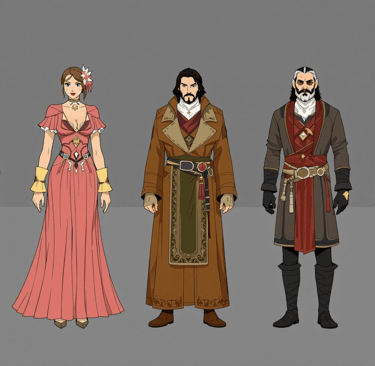

Every great story is built on compelling characters—figures who captivate us, inspire us, or even make us question our beliefs. But if you look closely at literature, mythology, and modern storytelling, you’ll notice something intriguing: certain character types appear again and again across cultures, genres, and eras. These recurring character patterns are known as archetypes.

Archetypes are fundamental character models that embody specific traits, motivations, and narrative functions. They serve as the foundation for some of the most unforgettable characters in fiction, from ancient myths to contemporary novels. We recognize them instinctively—the brave hero on a perilous journey, the wise mentor offering guidance, the cunning trickster who disrupts the norm. These archetypes resonate deeply because they reflect universal aspects of human nature and the struggles we all face.

The Origins of Archetypes: Why Are They Universal?

The concept of archetypes dates back to Carl Jung, the Swiss psychologist who first identified them as part of the collective unconscious—a shared reservoir of symbols, images, and character types that humanity has inherited over time. Jung believed these archetypes emerge naturally in myths, dreams, and literature, shaping the way we understand human behavior and storytelling.

But the use of archetypes predates psychology. Long before Jung, Aristotle analyzed recurring character roles in Greek tragedies. Later, Joseph Campbell expanded on these ideas in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, outlining the monomyth (or The Hero’s Journey), which reveals how mythological heroes from different cultures follow similar narrative patterns. From Gilgamesh to Luke Skywalker, from Odysseus to Katniss Everdeen, character archetypes have endured because they mirror the way we process and interpret the world.

Why Do Archetypes Matter in Storytelling?

Archetypes give stories structure and emotional weight. They offer a shorthand for character development while allowing for endless variation and creativity. A well-written archetype feels both familiar and fresh, giving readers an immediate sense of who a character is, while also allowing room for surprise and depth.

For authors, understanding archetypes is incredibly valuable. They provide a framework for building compelling characters while avoiding the pitfalls of one-dimensional storytelling. A strong archetype ensures that your characters have clear motivations, consistent behaviors, and a dynamic role within the narrative.

What Archetypes Are NOT

Despite their importance, archetypes are often misunderstood. Here’s what they are not:

They are not stereotypes. While archetypes represent recurring patterns, they are not rigid, shallow clichés. A stereotype is a flattened, exaggerated representation of a group, while an archetype is a foundational model that allows for complexity and nuance. For example, the Mentor archetype is not just "an old wise man"; he can be an eccentric scientist, a reluctant teacher, or even a mystical spirit.

They are not fixed roles. Characters can evolve or shift between archetypes throughout a story. A Hero may become a Villain, a Mentor may turn into a Shadow, and a Trickster may develop into an Ally. These transformations create some of the most compelling narratives in fiction.

They do not replace originality. Archetypes are tools, not templates. The goal is not to fit characters neatly into boxes, but to understand their underlying purpose so you can create fresh, engaging stories. Two authors can write vastly different versions of the same archetype, bringing unique perspectives, conflicts, and personalities to the character.

How Are Archetypes Used in Fiction?

Archetypes help shape a character’s role in the narrative. Some characters exist to drive the plot (like the Hero), while others serve to challenge or aid the protagonist (like the Shadow or Mentor). Understanding these functions helps authors craft balanced, engaging stories where every character has a meaningful place.

Archetypes also tap into reader expectations. Audiences instinctively recognize these character types, allowing them to connect more easily with the story. When a character defies expectations within an archetype—such as an Anti-Hero who is morally ambiguous or a Shadow who is sympathetic—it adds depth and intrigue to the narrative.

Now that we’ve explored what archetypes are and why they matter, let’s dive into the major character archetypes in fiction—their traits, motivations, and how they shape storytelling.

1. The Hero

Role in Storytelling:

The Hero is the protagonist of the story, embarking on a journey that challenges their physical, emotional, or moral limits. They strive to achieve a goal, overcome adversity, and often experience profound personal growth. Their journey is typically framed around the Hero’s Journey—a narrative structure made famous by Joseph Campbell.

Core Traits:

Courageous and determined – Faces challenges head-on, often against overwhelming odds.

Moral and selfless – Usually driven by a sense of justice, honor, or responsibility.

Resilient and adaptable – Learns from failures and continues despite setbacks.

Relatable flaws – Struggles with self-doubt, fear, or personal weaknesses, making them human and compelling.

Motivations:

To prove their worth or identity.

To protect loved ones or society at large.

To fulfill a prophecy or destiny.

To seek redemption for past mistakes.

Variations of the Hero Archetype:

The Classic Hero: Embodies traditional heroic qualities, such as King Arthur or Superman.

The Tragic Hero: Doomed by a personal flaw, like Hamlet or Anakin Skywalker.

The Reluctant Hero: Resists the call to adventure but eventually accepts it, such as Bilbo Baggins or Katniss Everdeen.

The Anti-Hero: Operates in morally gray areas, like Walter White or Deadpool.

2. The Mentor

Role in Storytelling:

The Mentor is a guiding figure who provides wisdom, training, and insight to the Hero. They often serve as the Hero’s moral compass, helping them grow and prepare for their challenges. Sometimes, the Mentor’s death acts as a catalyst for the Hero’s transformation.

Core Traits:

Wise and experienced – Possesses knowledge that the protagonist lacks.

Patient and encouraging – Supports and motivates the Hero.

Sacrificial and selfless – Often puts the Hero’s success above their own survival.

Flawed but insightful – May struggle with past failures or regrets.

Motivations:

To pass on knowledge before their time runs out.

To correct a past mistake through the Hero.

To protect and guide the Hero on their journey.

Variations of the Mentor Archetype:

The Wise Old Sage: Aged and knowledgeable, like Gandalf or Yoda.

The Fallen Mentor: Has a tragic past or questionable morals, such as Severus Snape.

The Comedic Mentor: Uses humor and unconventional methods to teach, like Master Roshi in Dragon Ball.

The Dark Mentor: Pushes the Hero toward a darker path, like Emperor Palpatine.

3. The Shadow (Villain)

Role in Storytelling:

The Shadow represents the story’s primary source of conflict, serving as the antagonist to the Hero. They embody the Hero’s greatest fears, weaknesses, or the darker aspects of their own personality. The Shadow exists to challenge the Hero, often acting as a mirror of what the protagonist could become.

Core Traits:

Powerful and influential – Commands fear, respect, or control.

Driven and relentless – Pursues their goals with unwavering focus.

Intelligent and strategic – Uses manipulation, deception, or brute force.

Charismatic or terrifying – Engages audiences, whether through charm or menace.

Motivations:

To seek revenge for past wrongs.

To establish dominance or power.

To fulfill a twisted sense of justice or ideology.

To create chaos for personal enjoyment.

Variations of the Shadow Archetype:

The Evil Overlord: A dominating figure, like Sauron or Darth Vader.

The Corrupt Authority: A leader who exploits their power, like President Snow.

The Personal Nemesis: Someone with a deep personal connection to the Hero, like Moriarty.

The Sympathetic Villain: Has noble goals but twisted methods, like Erik Killmonger.

The Trickster: Chaos and Transformation

Role in Storytelling

The Trickster archetype introduces humor, chaos, or unpredictable elements into a story. They often challenge authority, expose hypocrisy, or act as wildcards that disrupt the status quo. Tricksters might be allies, villains, or something in between, but they always keep the story dynamic.

Core Traits

Clever and deceptive: Tricksters rely on wit and cunning.

Unpredictable: They challenge expectations and disrupt order.

Playful, sometimes irreverent: They often use humor to undermine serious situations.

Boundary-breakers: Tricksters defy rules and question norms.

Motivations

To expose the truth (e.g., The Joker in The Dark Knight).

To entertain themselves (e.g., Loki in Thor).

To bring about transformation (e.g., Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

Variations of the Trickster Archetype

The Comic Relief Trickster – Brings humor but doesn’t alter the plot much (e.g., Olaf in Frozen).

The Chaotic Trickster – Disrupts order, often with unintended consequences (e.g., Loki in Norse Mythology).

The Trickster Mentor – Teaches through deception (e.g., Rumpelstiltskin).

The Everyman: The Relatable Character

Role in Storytelling

The Everyman is the character who represents the average person, someone the audience can easily relate to. Unlike the Hero, who is often extraordinary in some way, the Everyman is defined by their ordinariness. They are not particularly powerful, skilled, or destined for greatness, yet they find themselves in extraordinary circumstances. Their appeal comes from their familiarity—they react to events in ways that feel realistic and grounded.

The Everyman often serves as a proxy for the reader, helping them navigate unfamiliar or high-stakes worlds. They provide a lens through which grand events and conflicts can be understood from a normal person’s perspective.

Core Traits

Relatable and unremarkable – They don’t stand out but are easily likable.

Resilient and adaptable – They find ways to cope despite lacking special abilities.

Good-hearted and well-intentioned – They strive to do the right thing, even if they’re unsure how.

Curious but cautious – They are often hesitant when faced with danger or change.

Motivations

To return to normal life after being thrown into chaos.

To protect or support loved ones.

To understand and make sense of their new circumstances.

To prove that even an ordinary person can make a difference.

Variations of the Everyman Archetype

The Fish Out of Water – Someone completely unprepared for their new environment (e.g., Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy).

The Reluctant Hero – An Everyman who is forced into a heroic role (e.g., Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit).

The Comic Everyman – A character whose reactions to bizarre events provide humor (e.g., Jim Halpert in The Office).

The Rebel: The Status-Quo Challenger

Role in Storytelling

The Rebel archetype is defined by their resistance to authority, oppression, or societal expectations. They challenge the status quo and fight against injustice, corruption, or tyranny. Often, Rebels exist in dystopian, oppressive, or unjust worlds, but they can also simply be rule-breakers in otherwise normal settings.

Rebels are complex characters—some are noble freedom fighters, while others are chaotic and unpredictable. Their defining characteristic is their refusal to conform, even if it costs them dearly.

Core Traits

Independent and defiant – They do things their own way, no matter the cost.

Passionate and determined – Their beliefs drive them forward.

Brave and reckless – They take risks to achieve their goals.

Often anti-heroes – They don’t always follow traditional morality.

Motivations

To overthrow or disrupt a corrupt system.

To fight for personal freedom.

To avenge a personal injustice.

To expose lies or hidden truths.

Variations of the Rebel Archetype

The Revolutionary – A freedom fighter against tyranny (e.g., Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games).

The Anti-Hero Rebel – A morally gray figure challenging authority (e.g., Han Solo in Star Wars).

The Rogue – A troublemaker who acts on impulse (e.g., Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean).

The Explorer: The Seeker of New Horizons

Role in Storytelling

The Explorer is driven by a desire for adventure, discovery, and the pursuit of knowledge. They are not content with staying in one place or following the status quo—they must venture into the unknown. Whether they seek physical locations, new experiences, or inner understanding, Explorers challenge the boundaries of their world.

Explorers are often seen in adventure stories, but they also appear in narratives about self-discovery.

Core Traits

Curious and open-minded – Always seeking something new.

Independent and restless – Discontent with stagnation.

Adventurous and fearless – Willing to take risks for discovery.

Occasionally reckless – Their thirst for adventure can lead them into danger.

Motivations

To explore new lands or cultures.

To find deeper meaning or purpose.

To seek truth or forbidden knowledge.

To escape monotony and experience the world.

Variations of the Explorer Archetype

The Adventurer – A physically daring explorer (e.g., Indiana Jones in Indiana Jones).

The Self-Seeker – Someone searching for personal meaning (e.g., Moana in Moana).

The Scientist/Philosopher – Someone driven by intellectual curiosity (e.g., Victor Frankenstein in Frankenstein).

The Caregiver: The Nurturing Protector

Role in Storytelling

The Caregiver archetype is defined by their compassion, selflessness, and desire to protect others. They provide emotional and physical support, often putting others' needs before their own.

Caregivers can be parental figures, best friends, healers, or even warriors driven by the desire to shield others from harm.

Core Traits

Loving and nurturing – They give without expecting anything in return.

Loyal and devoted – They will go to great lengths to protect their loved ones.

Self-sacrificing – They often neglect their own needs.

Strong yet gentle – They balance warmth with resilience.

Motivations

To protect or heal those in need.

To provide emotional support to struggling characters.

To keep a family, community, or team together.

To find fulfillment through helping others.

Variations of the Caregiver Archetype

The Parental Caregiver – A mother or father figure (e.g., Marmee March in Little Women).

The Devoted Companion – A best friend or sidekick who supports the Hero (e.g., Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings).

The Warrior Caregiver – Someone who protects through strength (e.g., Brienne of Tarth in Game of Thrones).

The Ruler: The Authority Figure

Role in Storytelling

The Ruler archetype represents power, leadership, and control. Whether they are a benevolent king, a ruthless dictator, or a corporate CEO, they seek order and stability. They often face dilemmas about how to wield power—should they rule with kindness or an iron fist?

Rulers can be mentors, protagonists, or villains, depending on their values and how they use their authority.

Core Traits

Commanding and authoritative – Naturally assumes leadership roles.

Strategic and disciplined – Plans meticulously for long-term stability.

Responsible but burdened – Feels the weight of leadership.

Can be controlling or paranoid – Fears losing power or being betrayed.

Motivations

To maintain or expand their power.

To protect their kingdom, company, or domain.

To impose order and prevent chaos.

To leave a lasting legacy.

Variations of the Ruler Archetype

The Benevolent Leader – Uses power wisely for the good of others (e.g., Mufasa in The Lion King).

The Tyrant – Obsessed with control, ruling through fear (e.g., Tywin Lannister in Game of Thrones).

The Corrupt CEO/Politician – Uses power for personal gain (e.g., President Snow in The Hunger Games).

The Creator: The Visionary Innovator

Role in Storytelling

The Creator archetype is driven by imagination, invention, and artistic expression. They are the builders, inventors, and dreamers who bring new ideas to life. However, their obsession with perfection can lead to their downfall.

Creators are often scientists, artists, or entrepreneurs who struggle with the impact of their work.

Core Traits

Imaginative and visionary – Always sees possibilities beyond the ordinary.

Passionate but obsessive – Devoted to their craft, sometimes at a personal cost.

Driven by curiosity – Always searching for the next breakthrough.

Struggles with imperfection – Can be a perfectionist or overly critical of their own work.

Motivations

To create something meaningful or revolutionary.

To prove their brilliance to the world.

To leave a lasting artistic or scientific legacy.

To achieve perfection in their craft.

Variations of the Creator Archetype

The Genius Inventor – Pushes technological boundaries (e.g., Tony Stark in Iron Man).

The Mad Scientist – Becomes obsessed with creation, ignoring consequences (e.g., Victor Frankenstein in Frankenstein).

The Visionary Artist – Focuses on personal expression (e.g., Leonardo da Vinci in historical fiction).

The Magician: The Mystic and Transformer

Role in Storytelling

The Magician archetype possesses knowledge, wisdom, or supernatural power, often serving as a guide or catalyst for transformation. They understand hidden truths and use their insights to shape reality, whether through literal magic or strategic manipulation.

Magicians can be wise mentors or dangerous figures, depending on their moral alignment.

Core Traits

Intelligent and insightful – Sees beyond the surface of reality.

Mysterious and enigmatic – Often shrouded in secrecy.

Powerful and influential – Commands great respect or fear.

Can be manipulative – Uses knowledge to control situations or people.

Motivations

To uncover and share wisdom.

To shape events from behind the scenes.

To gain ultimate knowledge or enlightenment.

To control fate or change destiny.

Variations of the Magician Archetype

The Wise Mentor – Guides the hero with knowledge (e.g., Dumbledore in Harry Potter).

The Trickster Magician – Uses illusions and deception (e.g., Loki in Thor).

The Dark Sorcerer – Seeks ultimate power (e.g., Emperor Palpatine in Star Wars).

The Lover: The Passionate Romantic

Role in Storytelling

The Lover archetype is motivated by emotion, passion, and relationships. They seek deep connections, whether romantic, familial, or platonic. Their strength lies in their ability to inspire others, but their deep emotions can also lead to heartbreak or self-destruction.

Lovers are often found in romance stories, but they also appear in epics, tragedies, and character-driven dramas.

Core Traits

Emotional and expressive – Wears their heart on their sleeve.

Loyal and devoted – Will sacrifice everything for love.

Romantic and idealistic – Sees love as a transformative force.

Can be impulsive – Acts on emotion rather than logic.

Motivations

To find or protect love.

To experience deep emotional fulfillment.

To fight for a relationship or connection.

To overcome loss or heartbreak.

Variations of the Lover Archetype

The Star-Crossed Lover – Faces obstacles that keep them apart (e.g., Romeo & Juliet).

The Devoted Partner – Willing to fight for their love (e.g., Jack Dawson in Titanic).

The Temptress/Charmer – Uses love or attraction to manipulate (e.g., Helen of Troy).

The Jester: The Comic Relief with Depth

Role in Storytelling

The Jester archetype brings humor, wit, and playfulness to a story. They lighten tense situations and often serve as truth-tellers, exposing hidden realities through humor. Despite their comedic nature, Jesters can have profound depth and wisdom.

Jesters aren’t always comic relief; sometimes, they use humor to mask pain or question authority in a way others can’t.

Core Traits

Clever and quick-witted – Uses humor to navigate life.

Playful and mischievous – Enjoys shaking things up.

Honest but tactless – Says things others won’t.

Can hide sadness behind laughter – Uses comedy as a coping mechanism.

Motivations

To entertain and amuse.

To challenge authority in a way that is socially acceptable.

To mask personal pain through humor.

To expose uncomfortable truths through satire.

Variations of the Jester Archetype

The Trickster – Causes chaos with pranks and mischief (e.g., The Genie in Aladdin).

The Wise Fool – Appears foolish but has deep insight (e.g., Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones).

The Sarcastic Sidekick – Uses humor to deflect emotions (e.g., Deadpool).

Beyond the Basics: Combining and Subverting Archetypes

Archetypes are powerful tools, but real, memorable characters often go beyond a single template. They combine elements of multiple archetypes or subvert traditional expectations to create something fresh and engaging. Let’s explore how you can do this in your own writing.

Blending Archetypes for Complex Characters

While each of the 12 classic archetypes serves a distinct role, real people are rarely one-dimensional. The best fictional characters often embody aspects of multiple archetypes, creating deeper personalities and richer storytelling.

Here’s how blending archetypes works in practice:

A Hero with Mentor-like Traits – Some protagonists not only seek adventure but also act as guides for others. This blend creates leader-heroes like Aragorn (The Lord of the Rings), who is both a warrior and a source of wisdom for his companions.

A Trickster with a Heart of Gold – A character may initially seem like a Jester but reveal layers of depth over time. Tyrion Lannister (Game of Thrones) uses sarcasm and humor, but he is also deeply strategic and empathetic.

A Ruler Who is Also a Caregiver – Leaders like Mufasa (The Lion King) balance the strength of a Ruler with the nurturing qualities of a Caregiver.

An Anti-Hero with a Magician’s Mindset – Walter White (Breaking Bad) blends the intelligence of a Magician with the moral ambiguity of an Anti-Hero, making him an unpredictable yet compelling protagonist.

When combining archetypes, ask yourself:

How do these traits complement each other?

How do they clash and create internal conflict?

How does this combination make the character unique?

Subverting Archetypes: Playing Against Expectations

Subverting an archetype means challenging the audience’s preconceived notions about what a character should be. This technique is incredibly effective for creating fresh, dynamic characters.

Here are some common ways archetypes can be subverted:

The Reluctant Hero – Instead of bravely accepting their fate, this Hero resists the call to adventure. Bilbo Baggins (The Hobbit) prefers a quiet life, only embarking on his journey after much persuasion.

The Villain with Noble Motives – Rather than being purely evil, some Shadows believe they are acting for the greater good. Killmonger (Black Panther) has a sympathetic goal—helping oppressed people—but his methods make him the antagonist.

The Wise Mentor Who Fails – Instead of being all-knowing, some mentors have their own flaws and blind spots. Dumbledore (Harry Potter) withholds crucial information from Harry, making questionable decisions that shape the story.

The Jester Who Becomes the Most Serious Character – Some comic relief characters undergo profound transformations, revealing their hidden depth. In The Last of Us, Ellie starts as a snarky, comedic character but grows into a hardened survivor.

When subverting archetypes, consider:

What expectations does this archetype set for the audience?

How can you flip those expectations while maintaining a believable character arc?

How does this subversion enhance your story’s themes?

Creating Fresh Takes on Classic Archetypes

If you want to craft a character that feels fresh yet familiar, try these strategies:

Change the Context – A traditional archetype can feel new if placed in an unexpected setting. A Magician in a sci-fi world (Dr. Strange in the Marvel Universe), a Jester in a horror story (*Pennywise in IT), or a Ruler in exile (Black Panther).

Give Them an Unexpected Trait – Mix things up by giving your character an unusual quality. A Hero with crippling self-doubt, a Lover who is emotionally detached, or a Caregiver who is brutally honest.

Make Their Journey Unique – Even if your character fits a classic archetype, their experiences, relationships, and growth can make them stand out.

How to Use Archetypes in Your Own Writing

Now that you understand archetypes, let’s explore how to apply them effectively in your own storytelling.

Choosing the Right Archetypes for Your Story’s Themes

The best way to select an archetype is to align it with your story’s themes. Ask yourself:

What is the core conflict of my story?

What character type would best represent or challenge that conflict?

How do my character’s flaws and strengths reinforce my themes?

Examples of Theme-Based Archetype Choices:

If your story is about fighting oppression, a Rebel protagonist makes sense.

If it explores self-discovery, an Explorer or an Everyman would fit.

If it’s about legacy and responsibility, a Ruler struggling to balance power would be compelling.

Avoiding Stereotypes While Making Characters Feel Real

While archetypes provide a foundation, your goal should be to create well-rounded, multi-dimensional characters. Here’s how to avoid falling into stereotypical portrayals:

Give them flaws that contrast their strengths. A Caregiver might be overbearing. A Hero might have an ego problem.

Make them unpredictable. Have them react in unexpected ways, showing that they are not just a “type” but a unique individual.

Avoid clichés in dialogue and actions. Instead of having a Ruler say, “Because I am the king, that’s why,” show their leadership through decisions and conflicts.

Let them evolve. Even if they start as a strong archetype, their experiences should shape and challenge them.

Developing Character Arcs That Go Beyond the Archetype’s Core Traits

A character arc is what makes an archetype compelling—it’s how they change over the course of the story.

Three Common Character Arcs:

The Positive Arc – The character grows into their potential (e.g., Simba in The Lion King).

The Negative Arc – The character’s flaws consume them (e.g., Anakin Skywalker in Star Wars).

The Flat Arc – The character remains steadfast while changing the world around them (e.g., Captain America).

Ask yourself:

What is my character missing at the start?

What experiences force them to change?

How does the resolution reflect their internal growth?

Even if your character fits an archetype, their arc should make them feel unique.

Conclusion: Archetypes as a Starting Point, Not a Limitation

Archetypes Are Blueprints, Not Rigid Molds

The biggest takeaway is this: archetypes are tools, not rules. They are a starting point, but your creativity is what makes a character memorable. Don’t be afraid to mix, subvert, or reinvent archetypes to fit your vision.

The Importance of Unique Traits, Backgrounds, and Flaws

A well-crafted character should have:

A distinct voice (how they talk, think, and express themselves).

A unique backstory that explains their behavior.

Flaws and contradictions that make them feel human.

Final Call to Action: Experiment With Archetypes!

Now that you understand archetypes:

Try identifying them in your favorite books, movies, or TV shows.

Experiment with combining or subverting them in your writing.

Most importantly—have fun crafting characters that feel real, complex, and unforgettable.

What archetypes do you love writing the most? Which ones do you want to subvert in your next story? Start building your character today!